De-Identification vs Anonymization: Compliance Guide

Post Summary

De-identification removes specific identifiers but allows for potential re-identification, while anonymization irreversibly removes all identifiers, making re-identification impossible.

HIPAA governs de-identification in the U.S., while GDPR emphasizes anonymization in the EU.

De-identification retains data utility for research and analytics while reducing privacy risks.

Anonymization ensures maximum privacy protection and is ideal for public data sharing or global use.

De-identification risks re-identification, while anonymization may reduce data utility and require advanced techniques.

By treating HIPAA de-identified data as pseudonymized under GDPR, implementing safeguards, and using tools like Censinet RiskOps™ for risk management.

When handling sensitive data, the choice between de-identification and anonymization matters for compliance and research needs. Here's the key difference:

- De-identification removes specific identifiers (e.g., names, SSNs) but still carries a small risk of re-identification. It meets U.S. HIPAA standards for research use without patient consent.

- Anonymization alters data to make re-identification impossible, meeting stricter EU GDPR standards. Once anonymized, data is no longer considered "personal data."

Quick Overview:

- De-identification works well for detailed research (e.g., AI training, longitudinal studies) but requires strict controls to manage re-identification risks.

- Anonymization is better for public data sharing or global use but reduces data detail, which may limit research precision.

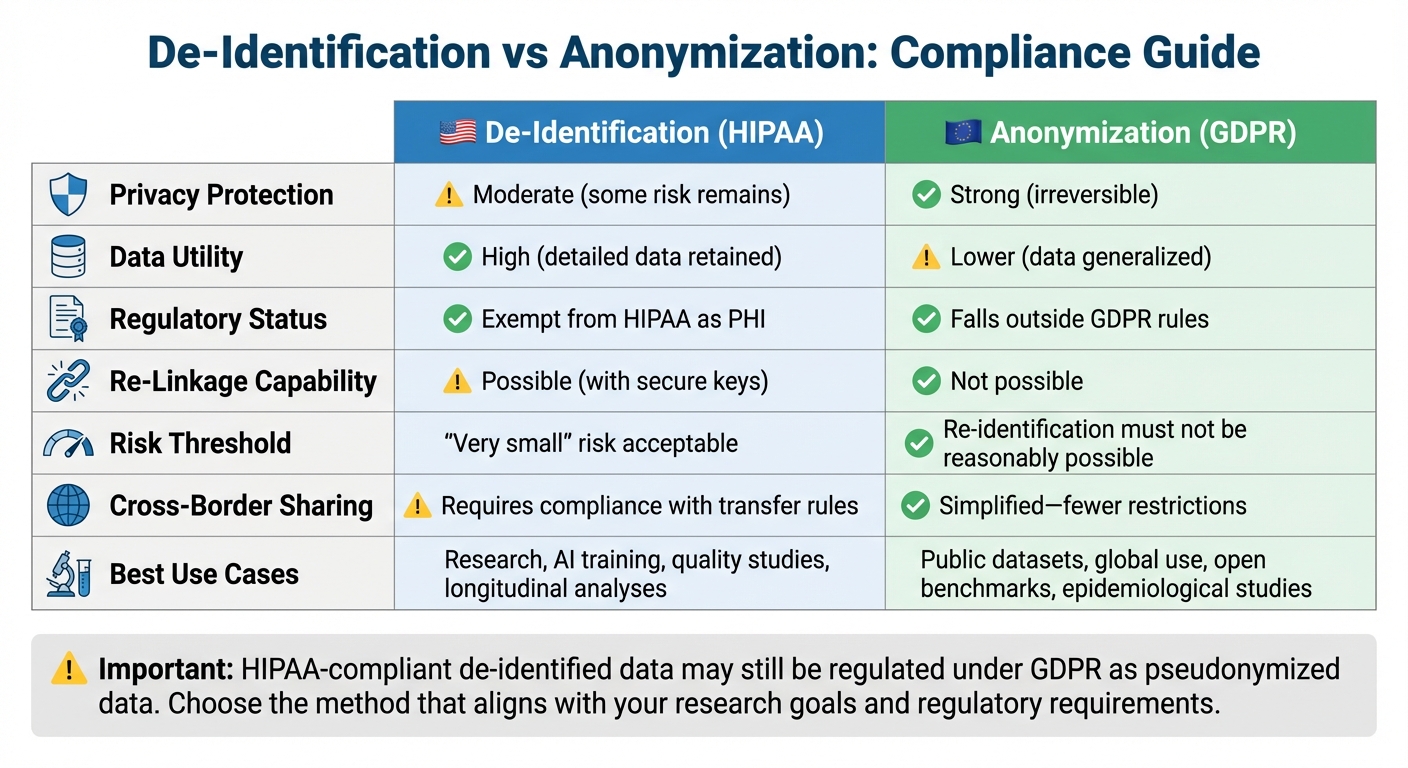

Quick Comparison:

| Aspect | De-Identification (HIPAA) | Anonymization (GDPR) |

|---|---|---|

| Privacy Protection | Moderate (some risk remains) | Strong (irreversible) |

| Data Utility | High (detailed data retained) | Lower (data generalized) |

| Regulatory Status | Exempt from HIPAA as PHI | Falls outside GDPR rules |

| Re-Linkage Capability | Possible (with secure keys) | Not possible |

| Best Use Cases | Research, AI, quality studies | Public datasets, global use |

For compliance in global research, HIPAA-compliant de-identified data may still be regulated under GDPR. Treating it as pseudonymized data under GDPR ensures stricter safeguards and prevents legal issues. Choose the method that aligns with your research goals and regulatory needs.

De-Identification vs Anonymization: HIPAA and GDPR Compliance Comparison

Regulatory and Compliance Requirements

HIPAA and GDPR take very different approaches to data protection, and understanding these distinctions is key when navigating compliance in international research. Under HIPAA, data is considered de-identified when it no longer identifies individuals and the risk of re-identification is minimal [2][5]. HIPAA provides two methods for achieving this: the Safe Harbor method and the Expert Determination method. The Safe Harbor method involves removing specific identifiers, while the Expert Determination method relies on a qualified expert applying scientific principles to ensure the risk of re-identification is minimal [2][5]. Once data meets these criteria, it is no longer considered Protected Health Information (PHI) and is exempt from most HIPAA Privacy Rule requirements. This sets the stage for examining how GDPR's stricter requirements differ.

GDPR, on the other hand, demands that anonymized data be irreversibly unidentifiable. Even a minimal risk of re-identification is unacceptable. The regulation draws a clear line between pseudonymized data and fully anonymized data. For GDPR, data must be processed in a way that makes it impossible to identify individuals using any methods that are reasonably likely to be employed - taking into account factors like cost, time, available technologies, and potential connections to other datasets [1][3]. If re-identification remains even remotely feasible, the data is classified as personal data and remains subject to GDPR rules, including requirements for a legal basis, data subject rights, and security obligations. Data that is de-identified under HIPAA might still be considered pseudonymized under GDPR [1][5].

This difference has important practical consequences. A dataset compliant with HIPAA could still pose risks under GDPR if any residual information allows for potential re-linkage [1][5]. For instance, device telemetry data with coded device IDs, timestamps, and hospital locations might meet HIPAA's Expert Determination criteria if re-identification risk is deemed very small. However, GDPR would classify such data as personal if realistic methods could re-link it to individuals [3][4][5].

For U.S. healthcare organizations working with EU-based partners, the challenge lies in designing data flows that meet both frameworks. The safest strategy often involves treating HIPAA de-identified data as pseudonymized personal data under GDPR if there is any residual re-identification risk [1][3][5]. This means establishing a lawful basis for processing in the EU, such as citing scientific research in the public interest, and implementing strong safeguards like encryption and access controls. Additionally, standard contractual clauses are often necessary for cross-border data transfers. To manage third-party risks in these complex scenarios, tools like Censinet RiskOps™ can help streamline vendor assessments and provide ongoing monitoring for third parties handling de-identified or pseudonymized patient data, PHI, or clinical application data.

| Aspect | HIPAA (United States) | GDPR (European Union) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Concept | De-identification of Protected Health Information (PHI) | Anonymization vs. pseudonymization of personal data |

| When Data Exits Scope | Once de-identified via Safe Harbor or Expert Determination with no actual knowledge of identifiability [5] | Only when truly anonymous - irreversibly non-identifiable by any party using reasonably likely means [1][3] |

| Risk Threshold | "Very small" risk of re-identification [5] | Re-identification must not be reasonably possible given all means likely to be used [1][3][5] |

| De-identified/Pseudonymized Status | De-identified PHI generally falls outside HIPAA [2][5] | Pseudonymized data remains personal data; GDPR fully applies [1][3] |

| Research Implications | De-identified datasets can be shared and used with minimal regulatory oversight | Pseudonymized research data requires legal basis, safeguards, and potentially Data Protection Impact Assessments |

1. De-Identification

Regulatory Compliance

In the U.S., de-identification is mainly regulated by HIPAA, which outlines two methods for removing Protected Health Information (PHI) from datasets. The Safe Harbor method involves eliminating 18 specific identifiers, such as names, geographic details smaller than a state (with some ZIP code exceptions), dates (except the year), phone numbers, email addresses, Social Security numbers, medical record numbers, and full-face photos [2]. Alternatively, the Expert Determination method allows a qualified expert to use statistical or scientific techniques to confirm that the risk of re-identification is "very small" [2][5]. Once either method is satisfied, the data is no longer considered PHI under HIPAA, exempting it from most Privacy Rule requirements [2].

However, even when data complies with HIPAA, it may still be classified as pseudonymized under GDPR. This classification requires organizations to establish a lawful basis for processing, honor data subject rights, and implement stricter security measures [1][3]. For healthcare organizations managing these overlapping regulations across multiple vendors and research collaborations, tools like Censinet RiskOps™ can simplify risk assessments and documentation for PHI and clinical data flows. This kind of structured approach is critical for addressing the potential reversibility risks in de-identified data.

Reversibility and Risk of Re-Identification

De-identification, while effective, is not foolproof. Research has shown that de-identified data can often be re-identified when combined with external datasets [1]. This means that such datasets carry residual risks, especially when public records like voter rolls are accessible. Instead of viewing de-identification as an absolute safeguard, organizations should treat it as a spectrum of risk. This involves assessing both the technical likelihood of re-linking data and contextual factors, such as the availability of external datasets and the potential for linkage attacks [1][3][4].

Keeping detailed records is crucial. Organizations should document the de-identification methods used, the assumed attacker model, any statistical risk assessments or expert evaluations, and the controls in place for managing re-identification keys (e.g., pseudonymization tables) [2][3][6]. Access to these keys should be tightly controlled, with logs and periodic reviews to account for new data sources that could enable re-identification [1][4][6].

Data Utility for Research

De-identification allows individual-level records to remain intact, making it more practical for research than full anonymization. Studies like longitudinal analyses, causal inference, and machine learning models benefit greatly from the detailed row-level data preserved through de-identification [1][3][4][6]. However, using generalized data - such as broad age ranges, vague geographic information, or approximate dates - can limit the precision needed for certain types of research, like rare disease studies or detailed spatiotemporal analyses [1][4][6].

To address this, many U.S.-based institutions use a tiered access model. Heavily de-identified datasets are often made available for exploratory research, while more detailed datasets are confined to secure environments with strict monitoring [3][6]. This approach helps balance compliance with the need for high-quality research data.

Cross-Border Data Sharing

Sharing de-identified data internationally adds another layer of complexity. While a dataset meeting HIPAA's Safe Harbor criteria may be considered de-identified in the U.S., it could still qualify as pseudonymous personal data under GDPR. This means organizations must establish a lawful basis for processing, conduct transfer impact assessments, and use mechanisms like standard contractual clauses to ensure compliance [3][7]. Often, data is stored in secure research environments where international collaborators can analyze results without direct access to row-level records [6].

To safeguard data, organizations should implement technical controls like encryption, role-based access, and audit logging. They should also establish organizational measures such as staff training, governance committees, and incident response plans. Contracts should explicitly prohibit re-identification attempts and prevent data from being linked to other datasets [1][2][3][4]. In cases of suspected re-identification, contracts should mandate prompt notification and remediation. Platforms like Censinet RiskOps™ can assist by standardizing security assessments, verifying control measures, and continuously monitoring risks tied to de-identified research data, PHI, and related data flows.

2. Anonymization

Regulatory Compliance

Anonymization is the process of altering data so that individuals cannot be identified, even when combined with other accessible information [1]. This involves the permanent removal of direct identifiers, like names and Social Security numbers, as well as indirect identifiers, such as specific ZIP codes, full birth dates, or unique combinations like birthdate, ZIP, and gender.

Under frameworks like the GDPR and similar international standards, data that meets strict anonymization criteria is no longer classified as personal data. This means it may no longer be subject to many data protection rules. In the U.S., while HIPAA doesn’t specifically define anonymization, data that cannot reasonably identify individuals - and where the entity has no knowledge of potential identification - may fall outside the scope of the Privacy Rule.

The advantages of compliance include more flexibility in sharing anonymized datasets across projects and borders, extended retention for secondary research, and the ability to use the data without requiring fresh consent. However, organizations must demonstrate that anonymization standards and safeguards have been met. For healthcare organizations managing multiple research collaborations and vendor relationships, platforms like Censinet RiskOps™ can help streamline security assessments and document controls over research datasets, even those containing partially anonymized or de-identified protected health information (PHI) and clinical data. Next, we’ll explore how these rigorous requirements influence the risk of re-identification.

Reversibility and Risk of Re-Identification

True anonymization ensures that no one - not even the data holder - can reasonably re-identify individuals, even if they have access to additional information that an attacker might realistically acquire [1]. Achieving this requires removing all identifying details and using techniques like generalization, aggregation, noise addition, or differential privacy.

Incomplete anonymization can leave patterns that allow re-identification through background knowledge attacks. For instance, a rare diagnosis in a small town could still pinpoint an individual, even after direct identifiers are removed. As the International Association of Privacy Professionals (IAPP) explains, "de-identification is not anonymization (in virtually all cases)." Organizations must carefully assess identifiers, evaluate the uniqueness of records, and analyze external risks. They must also document why any remaining identification risk is negligible, given the safeguards in place. Without measures like destroying mapping keys, enforcing re-identification bans in contracts, and implementing strong technical controls, regulators may classify the process as de-identification rather than true anonymization.

Data Utility for Research

While compliance sets the foundation, anonymization can impact the usefulness of data for research. Reducing data detail can limit its value for certain clinical or biomedical studies. Aggregated or generalized data might mask significant patterns, and techniques like noise addition or differential privacy can, if not carefully managed, introduce bias or weaken statistical accuracy.

To strike a balance between privacy and research needs, researchers can design studies around privacy-aware variables. For example, using broader categories like risk scores or comorbidity indices instead of raw data can protect privacy while retaining clinical relevance. Many U.S.-based institutions adopt a tiered access approach. Heavily anonymized summary datasets are shared widely, while more detailed, de-identified data is restricted to secure, tightly controlled environments. Privacy-preserving methods, such as those used in regression or survival analysis, also allow researchers to perform analyses without exposing individual-level data.

Healthcare organizations often choose anonymization for public data releases, open data platforms, and collaborative research across institutions. For internal studies requiring more granular data, robust de-identification methods and strict controls are typically employed. Engaging privacy experts and statisticians early in the research process can help balance privacy requirements with the need for detailed data.

Cross-Border Data Sharing

Anonymization also simplifies international data sharing. When data meets anonymization standards consistent with frameworks like the GDPR, it is generally treated as non-personal data. This can ease cross-border transfers, as many international data transfer rules and adequacy requirements apply only to personal data. Properly anonymized datasets can often be shared with European or other foreign research sites and hosted on U.S.-based or third-country platforms without triggering stringent transfer protocols.

However, challenges may arise if foreign regulators or ethics committees dispute whether the data is genuinely anonymized. In such cases, personal-data transfer rules might still apply. To avoid complications, U.S. sponsors should align their standards with the strictest applicable jurisdiction, conduct thorough threat modeling and risk assessments, and establish contracts that explicitly ban re-identification. U.S. healthcare entities under HIPAA, when partnering with EU or Canadian organizations, must also recognize that HIPAA-compliant de-identification (via Safe Harbor or Expert Determination) may not meet GDPR anonymization standards. This distinction underscores the differences in compliance requirements discussed earlier in this guide.

sbb-itb-535baee

Advantages and Disadvantages

When deciding between de-identification and anonymization in healthcare research, it’s all about finding the right balance between protecting privacy and maintaining the usefulness of the data. Each method has its own strengths and weaknesses, impacting compliance, data usability, and operational needs in different ways.

De-identification allows for the retention of detailed clinical, demographic, and temporal information while removing direct identifiers such as names or Social Security numbers. This level of detail is incredibly useful for projects like longitudinal outcomes research, training AI models, and quality improvement efforts that rely on patient-level insights. Additionally, de-identification can allow for secure re-linkage to original records when necessary for clinical follow-up, safety monitoring, or regulatory reporting. However, re-identification risks remain - studies show that it’s possible to match de-identified data with external datasets to re-identify individuals [1]. Because of this, de-identified data is still governed by data protection regulations like HIPAA and GDPR, requiring strict access controls, logging, and oversight of third-party vendors.

On the other hand, anonymization focuses on irreversible privacy protection, effectively removing the data from the scope of stringent regulations like GDPR. This simplifies international data sharing, long-term storage, and open-science initiatives, as there’s no need for ongoing consent or compliance with data transfer rules. Anonymization is particularly useful for public health dashboards, published benchmark datasets, and large-scale collaborations where individual follow-up isn’t needed. However, the trade-off is a loss in data granularity - the generalization, aggregation, or noise added during anonymization can obscure critical clinical patterns, hinder rare-event detection, and introduce bias into analyses. As the International Association of Privacy Professionals puts it, "de-identification is not anonymization (in virtually all cases)", highlighting the distinct differences in techniques and outcomes.

Here’s a quick comparison of these two approaches:

| Aspect | De-Identification | Anonymization |

|---|---|---|

| Privacy protection | Moderate - re-identification is possible using quasi-identifiers and external datasets | Strong - individuals cannot be re-identified by reasonable means |

| Data utility | High - detailed clinical, temporal, and demographic data is preserved | Lower - data is aggregated or generalized, reducing detail |

| Regulatory status | Treated as protected personal data under HIPAA, GDPR, etc. | Falls outside data protection laws when truly irreversible |

| Re-linkage capability | Possible via secure keys for follow-up or validation | Not possible - transformation is permanent |

| Cross-border sharing | Requires compliance with transfer rules and adequacy assessments | Simplified - fewer restrictions when data is no longer personal |

| Best use cases | Longitudinal studies, AI/ML training, quality improvement, vendor risk analytics | Public datasets, open benchmarks, epidemiological studies, educational use |

For research that requires detailed, linkable data within a controlled environment, de-identification - when done under HIPAA's Safe Harbor or Expert Determination standards - is often the better choice. Meanwhile, anonymization works best for scenarios where broad sharing and minimal oversight are priorities, and individual-level detail isn’t critical. Successfully implementing either method requires collaboration among researchers, compliance teams, and risk management experts to ensure proper safeguards are in place.

Conclusion

Deciding between de-identification and anonymization hinges on three key factors: regulatory requirements, research goals, and acceptable risk levels. De-identification involves removing or masking direct identifiers, such as names or Social Security numbers, but it doesn’t eliminate all re-identification risks - especially if the data can be linked to external sources. (This potential risk is explored further in the Introduction section.) On the other hand, anonymization transforms data to make re-identification virtually impossible, ensuring it falls outside the scope of most privacy laws.

Once data is de-identified under HIPAA’s Safe Harbor or Expert Determination, it’s no longer considered PHI (Protected Health Information). However, under GDPR, this same data may still be classified as pseudonymized [1][5]. For international research projects, particularly when data crosses borders or is widely shared, adhering to stricter standards - often GDPR-level anonymization - is typically the safer route.

When should you use each approach?

- Anonymization is ideal for publicly releasing data, sharing it with minimal restrictions, or removing it from regulatory oversight entirely. It works best when aggregate or generalized data can still support your research objectives.

- De-identification is more suited for scenarios requiring detailed, individual-level, or longitudinal data, such as clinical research, AI model training, or quality improvement initiatives. In these cases, strong access controls, data use agreements, and governance measures are crucial.

For healthcare organizations navigating complex vendor ecosystems and third-party risks, tools like Censinet RiskOps™ simplify cybersecurity and risk assessments for clinical applications, protected health information, medical devices, and supply chain vendors.

To maintain compliance while preserving data utility, it’s essential to document your decision-making process in impact assessments and research protocols. Engage with experts - such as privacy officers, legal counsel, data protection officers, security teams, and statisticians - to ensure a well-rounded approach. Keep in mind that neither de-identification nor anonymization is a one-time task. Both require ongoing, privacy-by-design strategies that balance compliance, data usability, and acceptable levels of residual risk.

FAQs

What’s the difference between de-identification and anonymization for compliance purposes?

De-identification involves taking steps to remove or obscure certain identifiers to lower the chances of linking data back to an individual. However, it’s important to note that this method doesn’t completely rule out the possibility of re-identification. To fully meet compliance standards like those outlined in HIPAA, additional measures might still be necessary.

Anonymization goes a step further by permanently and irreversibly stripping all identifying details, ensuring re-identification is impossible. While this offers a higher level of compliance confidence, it can also reduce the data's usefulness for research or analysis. The main difference between these methods lies in the level of re-identification risk and the permanence of the changes made to the data - both of which play a crucial role in shaping compliance strategies.

What’s the difference between how GDPR and HIPAA treat de-identified data?

GDPR views de-identified data as still potentially identifiable unless it meets stringent anonymization criteria. Under these standards, the data must be rendered completely unlinkable to any individual, with no possibility of re-identification. On the other hand, HIPAA considers data de-identified once specific identifiers are removed, meaning it is no longer classified as protected health information (PHI).

While HIPAA offers clear, step-by-step guidelines for de-identification, GDPR takes a more dynamic approach, focusing on ongoing risk assessment to ensure data remains anonymous and secure over time. This distinction underscores the importance for organizations managing sensitive information to thoroughly assess and align with the compliance demands of both frameworks.

When is it better to use anonymization instead of de-identification in research?

When your research calls for completely removing or permanently altering identifiable information, anonymization is the way to go. This ensures that individuals cannot be re-identified, which is crucial when strict privacy laws apply or when data is being shared with the public or outside organizations.

Anonymization offers a stronger layer of privacy protection than de-identification. It’s the best option for projects that need to meet rigorous data privacy standards or where minimizing the risk of re-identification is a top priority.

Related Blog Posts

Key Points:

What is the difference between de-identification and anonymization?

- De-Identification: Removes specific identifiers (e.g., names, SSNs) but retains some risk of re-identification. It is commonly used under HIPAA for research and analytics.

- Anonymization: Irreversibly removes all identifiers, ensuring that data cannot be re-identified. It meets stricter GDPR standards for privacy protection.

Which regulations govern de-identification and anonymization?

- HIPAA (U.S.): Defines de-identification through the Safe Harbor and Expert Determination methods, allowing data to be shared without being classified as PHI.

- GDPR (EU): Requires anonymization for data to fall outside its scope, ensuring no reasonable means of re-identification exist.

What are the benefits of de-identification?

- Data Utility: Retains detailed data for research, AI training, and longitudinal studies.

- Regulatory Compliance: Meets HIPAA standards for sharing PHI while minimizing privacy risks.

- Flexibility: Allows for controlled re-identification in secure environments.

What are the benefits of anonymization?

- Maximum Privacy: Eliminates re-identification risks, ensuring compliance with GDPR.

- Public Data Sharing: Ideal for open data initiatives and global collaborations.

- Regulatory Exemption: Anonymized data is no longer considered personal data under GDPR.

What are the challenges of de-identification and anonymization?

- De-Identification:

- Risk of re-identification if combined with external datasets.

- Requires robust safeguards like encryption and access controls.

- Anonymization:

- Reduces data granularity, limiting its utility for detailed research.

- Complex to implement, often requiring advanced techniques like differential privacy.

How can organizations ensure compliance with both HIPAA and GDPR?

- Treat De-Identified Data as Pseudonymized: Under GDPR, HIPAA-compliant de-identified data may still be considered personal data.

- Implement Safeguards: Use encryption, access controls, and secure environments for data sharing.

- Leverage Tools: Platforms like Censinet RiskOps™ streamline vendor assessments and ensure compliance with overlapping regulations.